The Band That Never Toured

The band onstage is Bikini Kill, a three-fourths-female group that recently relocated to DC from the small college town of Olympia, Washington. Bikini Kill has spent much of the past year on the road, building a fan base the way all independent bands cutting their teeth do in the early ‘90s: piling into a van and crisscrossing the country every few months, counting on a cassette-only demo they sell, and on word of mouth, to feed enthusiasm.

— from Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution

by Sara Marcus

Lately, I’ve been reading books that pull me back into the early nineties—the time of my youth, guitars, and the dream of being something bigger than a local musician. I just finished Kathleen Hanna’s Rebel Girl, about her years with Bikini Kill and beyond. Pair that with another music memoir, and suddenly I’m not just reading about that era, I’m living in it again. My own band days flood back with a mix of nostalgia and regret.

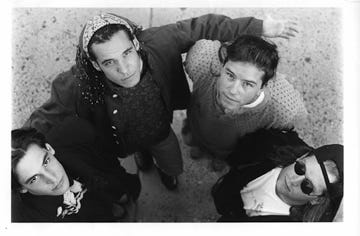

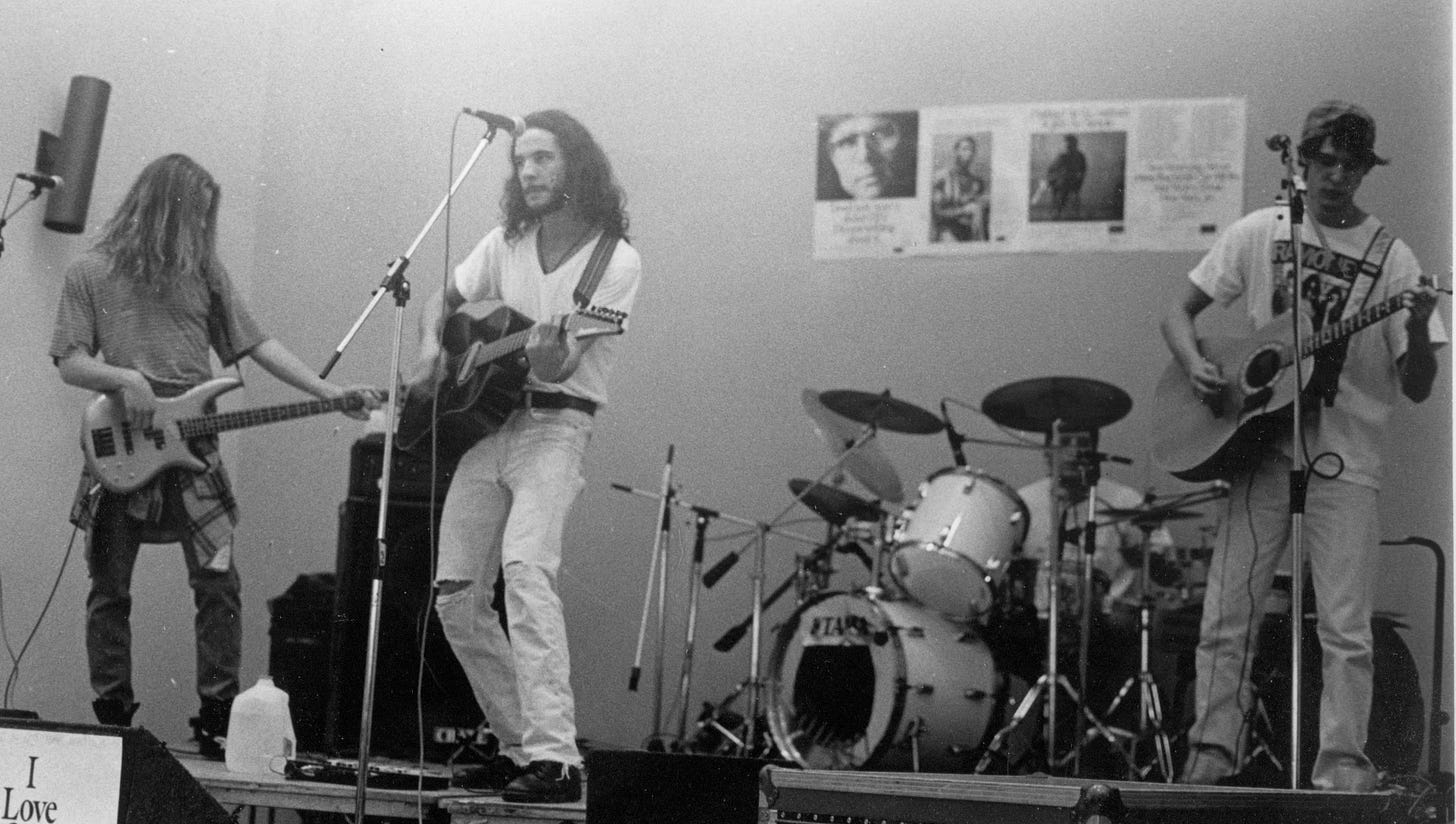

In the early nineties, I was in a band called Another Pretty Face. I hated the name then, and I still hate it now. But we were good—better than just another local cover band. We wrote our own music, played hard, and actually believed we had a shot. What we didn’t do, though, was pile into a van and chase the dream across the country. We didn’t tour. We discussed it, especially toward the end, but talk was all it ever amounted to. That decision—or indecision—is something that still gnaws at me.

It started with me writing songs in my bedroom. My brother, Nick, wanted to start a band; eventually, he wore me down. He became lead singer and rhythm guitarist; I took lead guitar. Members shifted in and out—Shane on drums, then Chuck, then Shane again; Sean on bass, then Steve. But the constant was my brother and me, pushing forward, playing community college gigs, seedy dive bars, even once under the escalator at Sears. We were raw, messy, but full of potential.

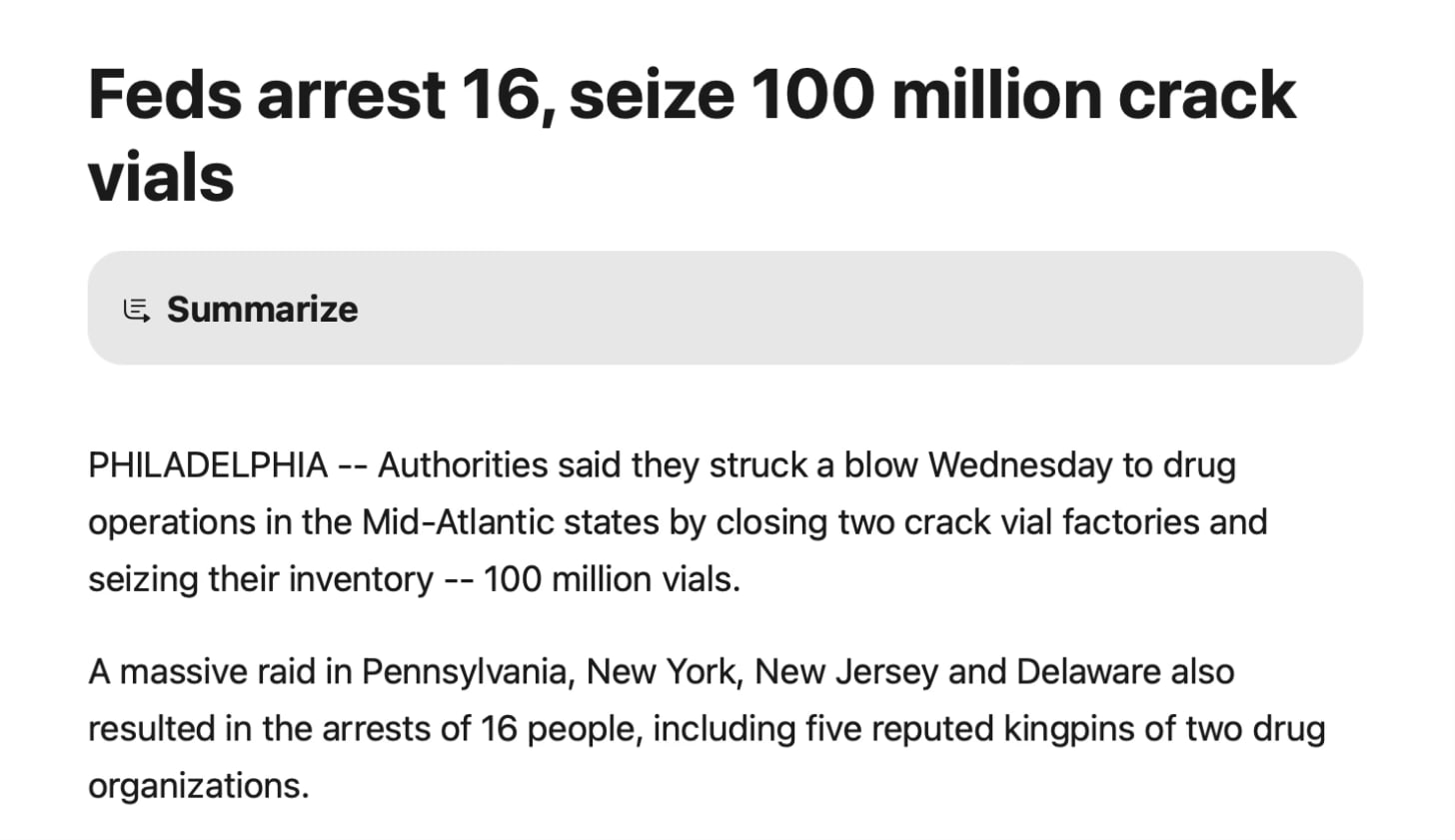

One of my first regrets was letting go of a friend from high school who had started managing us. He believed in us, hustled for gigs, and was hungry in a way we weren’t. But then came the Russians. Yes, Russians—this was right after the wall came down. They had money, big promises, and dangled opportunities in front of us: demos, videos, gigs, even the idea of playing in Russia itself. We traded loyalty for dollar signs, not knowing where that money was coming from, and of course, it blew up. The FBI eventually swooped in and shut down their operation. Just like that, everything collapsed.

We tried to recover, but I think that moment broke us. The trajectory had felt so upward, and when the rug was pulled, we didn’t have the resilience—or maybe the belief—to keep going on our own. That’s when the touring conversation came up. I wanted to hit the road, to take the risk, but not everyone agreed. We told ourselves we were getting older, that it was time to act like adults. The irony, of course, is that we were still so young. It was the perfect time to risk everything. Who knows—maybe we would have bumped into Bikini Kill on the road. Maybe we would have found our place.

Instead, our big finale was a backyard party. We played to a drunken crowd, and when we covered Creep by Radiohead, I knew in my gut it was over. I quit then and there. Not long after, I was hauling furniture across the country with my friend Anthony, working for Mayflower.

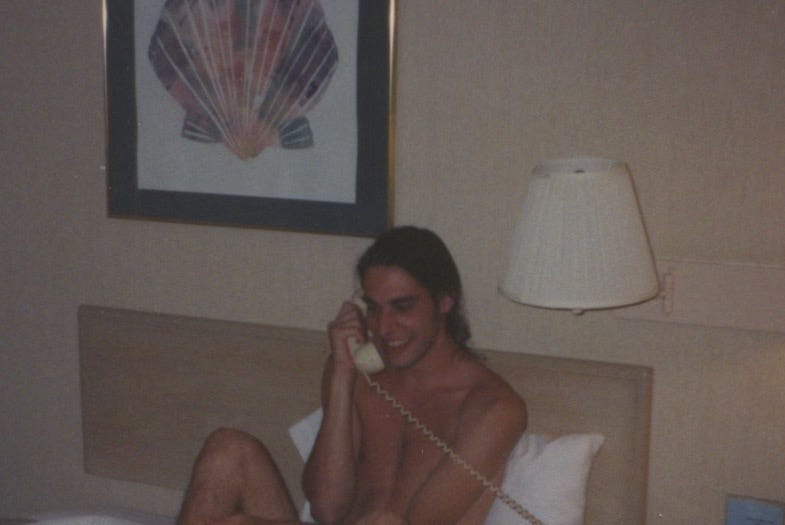

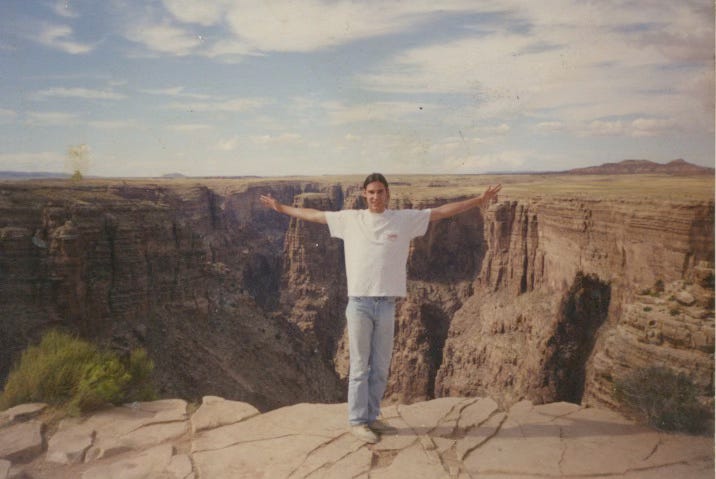

That cross-country trip was everything the band never was: spontaneous, freeing, irresponsible. I even remember sitting in a Las Vegas hotel, talking on the phone with my brother. He asked if I thought we’d get the band back together. I told him no. And I meant it.

Looking back, I know part of the problem was me. I wasn’t raised to take big risks. The idea of piling into a van with no money, no safety net, and no guarantee—it seemed reckless. But that recklessness was exactly what the dream demanded. I chose the responsible path, and I’ve been haunted by that choice ever since.

Regret is a strange thing. It doesn’t kill you, but it leaves holes—voids where you imagine the version of yourself that might have been. I live with those voids. I can picture the alternate universe where I did go on tour, where Another Pretty Face crisscrossed the country, maybe even made a name for ourselves. In that universe, I’m not reading Kathleen Hanna’s story and thinking, what if? I’m telling my own version of it.

But in this one, all I have is the band that never toured.