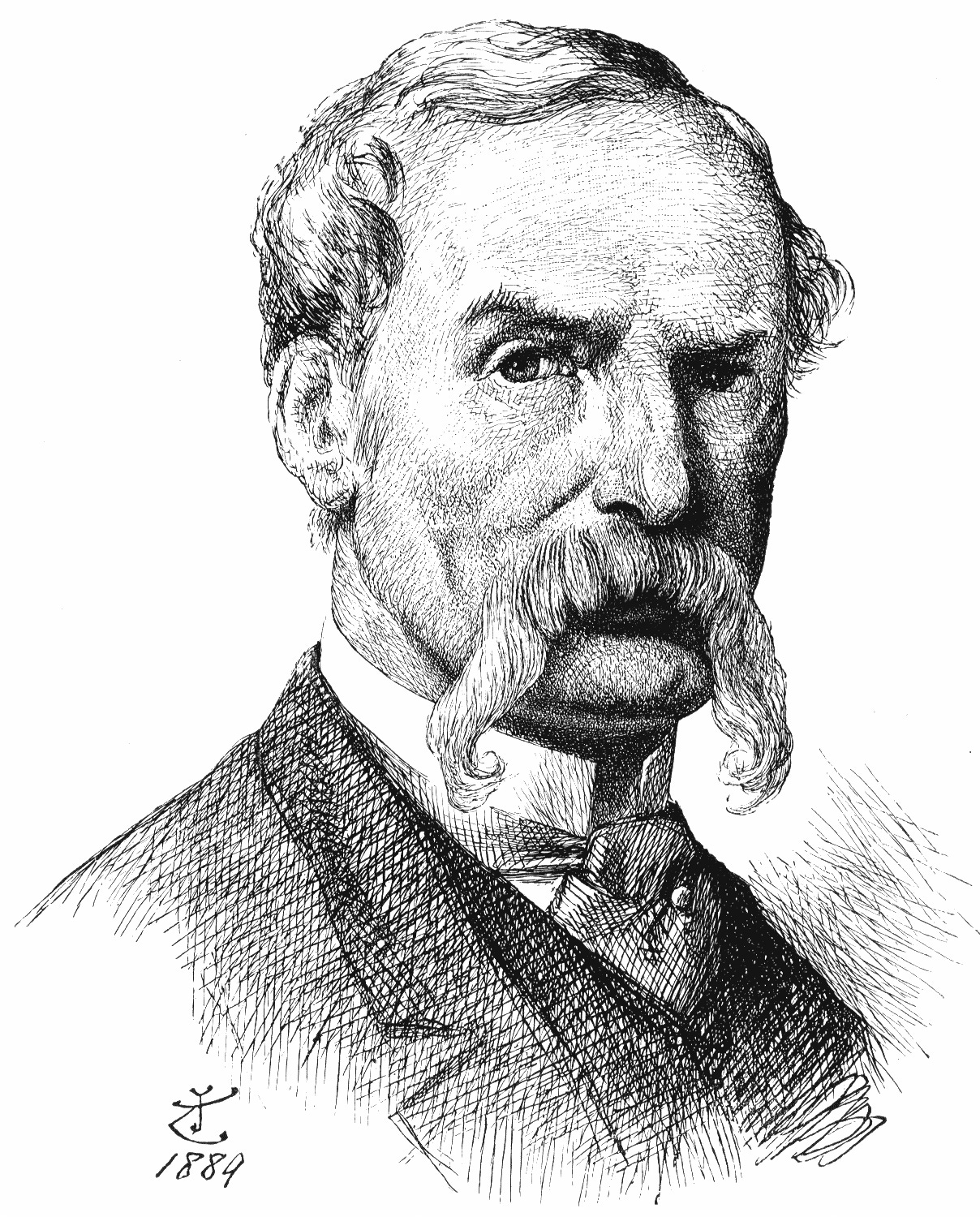

Before Alice was having tea with the Mad Hatter, Sir John Tenniel was skewering the politics of Victorian England with his satirical drawings in Punch magazine.

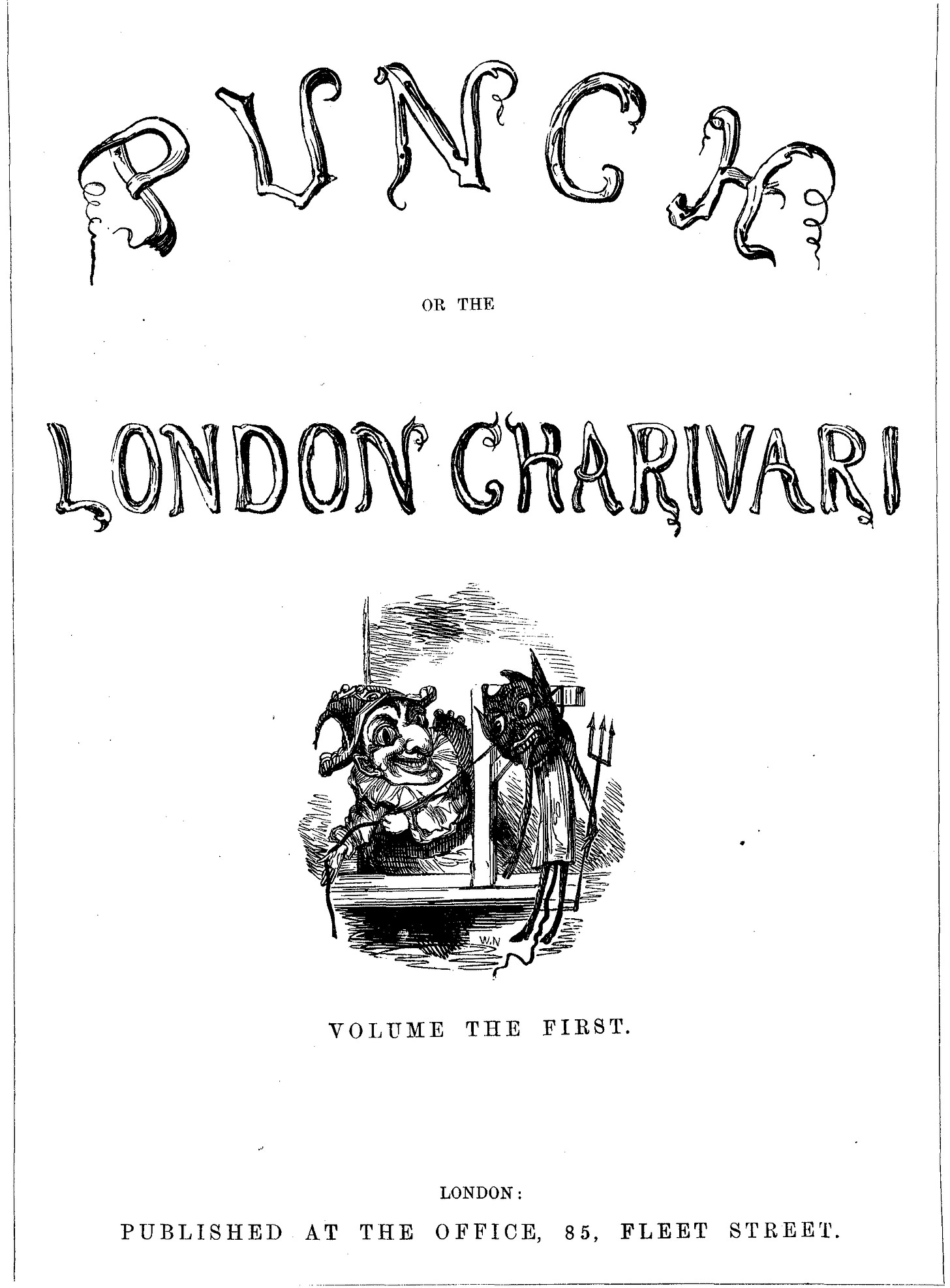

Although Tenniel had formal art training, he wasn’t a fan of how it was taught—so he taught himself. He was rumored to have a photographic memory and preferred to draw entirely from memory. Remarkably, he did all of this after losing the sight in one eye from a fencing accident in his youth, though he rarely mentioned it. It wasn’t long before he landed a job at Punch magazine, which you can think of as the internet of the Victorian era. His sharp, often biting cartoons gained widespread recognition and helped shape public opinion for decades.

What I found fascinating while learning about Tenniel is the evolution of the word cartoon. Originally, it referred to a preliminary sketch on paper—coming from the Italian cartone, meaning “paper.” But it wasn’t until Tenniel and Punch (and the satirical drawings of Victorian England) that the word took on its now-humorous meaning. By the 20th century, the term expanded again to include animation.

Although Tenniel is best known today as the illustrator for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, it’s important to remember that he was already famous in his own time as the lead political cartoonist for Punch—essentially the visual voice of 19th-century satire. Over his fifty years at Punch, he produced more than 2,000 cartoons.

That’s why, when Lewis Carroll was told his own drawings for Alice weren’t up to snuff, he was advised to hire a professional. Carroll, being an avid Punch reader, immediately thought of Tenniel.

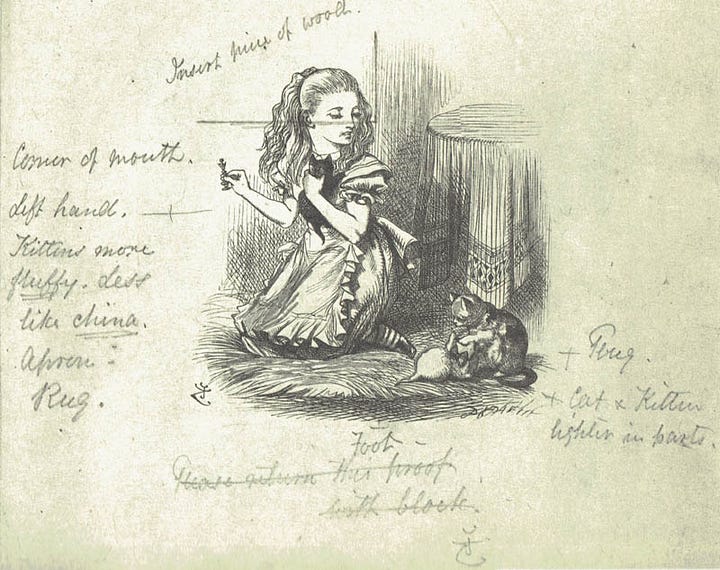

My research shows that Tenniel found Carroll to be… well, a bit of a nuisance. Carroll had something to say about nearly every drawing Tenniel produced—except for Humpty Dumpty, for some reason. The constant revisions drove Tenniel nuts. One argument even centered on Alice’s hair color: Carroll wanted brown, Tenniel insisted on blonde. We all know who won that one. It’s safe to say Tenniel defined the visual identity of Alice in Wonderland as we know it.

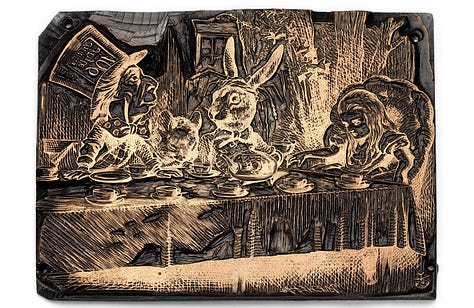

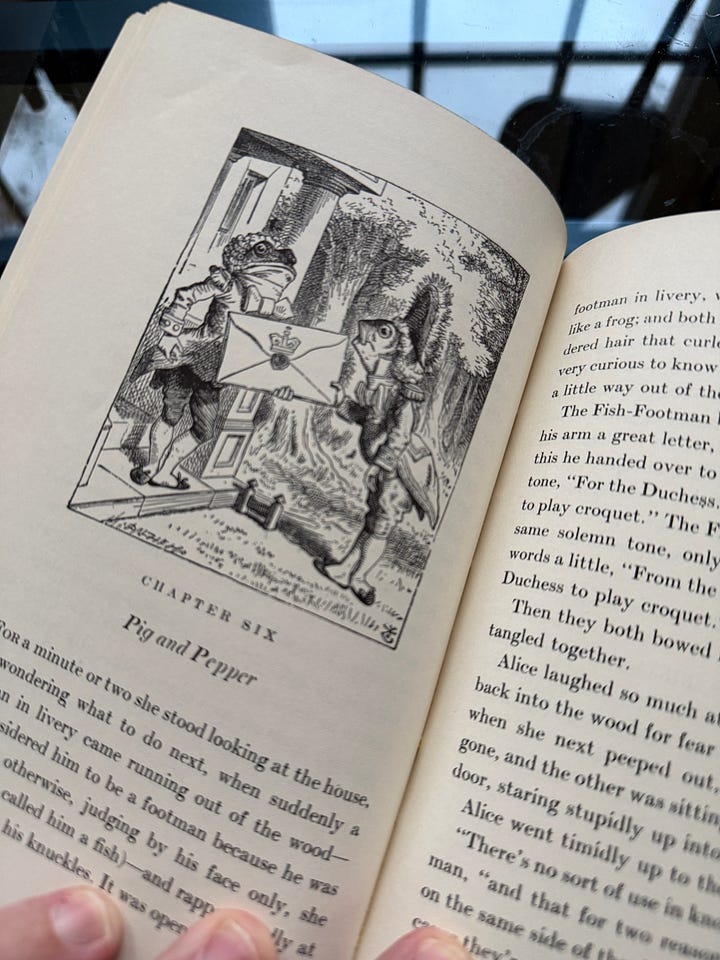

The art process for Alice was meticulous. Tenniel began with rough sketches, refined them, then traced and transferred the final design onto a wood block, where he redrew it carefully. From there, it went to the engravers—the Brothers Dalziel. Their company, which employed a team of artisans, would cut Tenniel’s lines into the wood block. It was an incredibly tedious process. Once completed, the wood was used as a master to create electrotype plates—metal copies used for printing. (Fun fact: those original wood blocks were thought lost to time until they were rediscovered in a bank vault in 1985.)

In 1893, Tenniel became the first cartoonist ever to be knighted. And while I think modern knighthood is a little silly, it’s still nice to see a cartoonist get that level of recognition. Tenniel’s work on Alice continues to be printed today, and his legacy at Punch runs deep—it’s in the DNA of modern satire and political cartoons. Maybe even in the DNA of Bud, Nick, and Joe.

If you enjoyed learning about John Tenniel, please subscribe. I’ll be sharing more stories about cartoonists and illustrators from history—because honestly, I just love learning about them.

A Related Thrift Store Find

While working on my short story, Malice in Wonderland, I found the centennial edition of Alice in Wonderland at the thrift store. These include Tenniel’s 92 drawings for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. It is one of my cherished book possessions.

Take it easy,

James